Can you tell us a bit about your production?

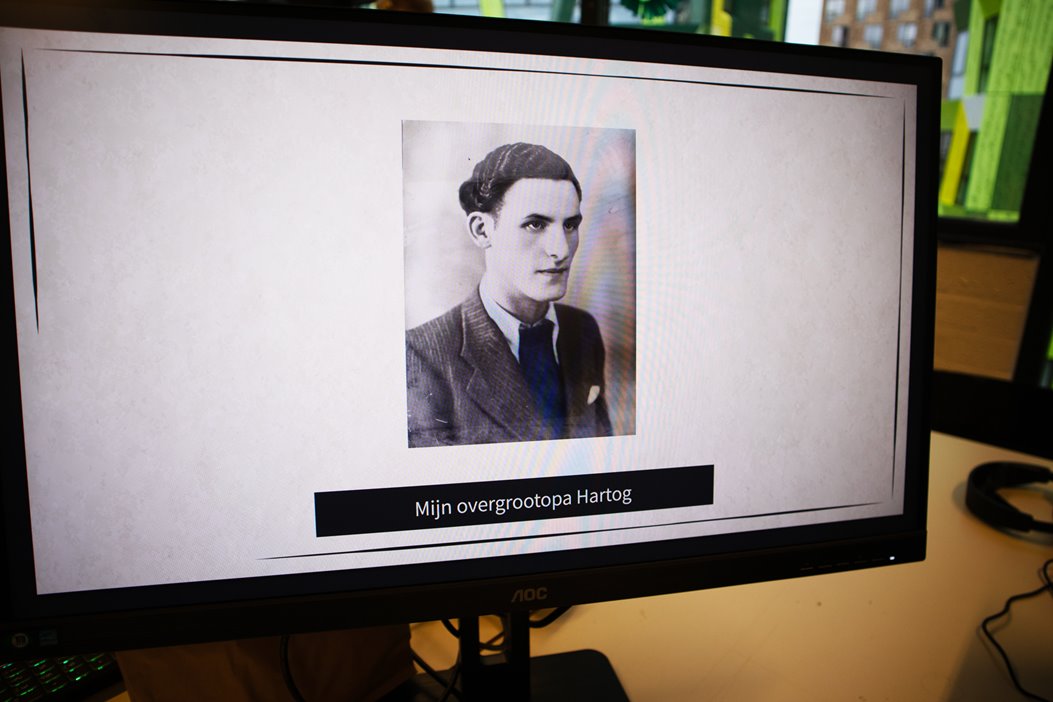

‘In the first chapter of the game, you get to know my grandparents very well. The war has not started yet at that moment. Hartog and Sientje are happy and in love. They live together and have a daughter, Ruby. But then the period starts of looming propaganda, with Jews becoming victims of violence, harassments and oppression. Not long after, their greatest fear becomes reality: the couple must give up their daughter and are deported to the Sobibor extermination camp, where they end in the gas chambers. The player of the game goes through each of these phases as they guide Hartog and Sientje towards their final days. This makes the experience all the more personal. Onthecht shows how a happy everyday life can suddenly turn into hell.’

Why did you want to make this game?

The goal behind the holocaust was to erase an entire group of people. Documents, photos, and personal possessions of the victims were destroyed or sold off. All to make it seem like they had never existed. I wanted to counter this, by giving a voice to my great grandparents; to make the memory of them tangible again. For myself as well, because I hardly had any idea about them. For me, it was in part also a processing of an intergenerational trauma.’

What did this trauma processing look like?

‘For this game, I partnered up with the Sobibor Foundation. This enabled me to watch lots of books, documentaries and reports. I learned every detail about the death of my great-grandparents. Horrible details: how they were murdered, how long it took and what the gas chambers looked like. It was quite a shock. Although I am personally the third generation of war victims, I had never considered myself to be an actual victim. Neither had I expected to be so strongly affected by the process. It might sound odd, but eventually my research did cause me to be able to cope with the facts. I was able to form a perspective and come to face with what really happened.’